As avant-garde artists in the late 1960s were abandoning commercial television in favor of video art, one artist continued to engage it directly: Andy Warhol. Warhol viewed television as an extension of his creative and political practice as an award-winning designer for CBS and NBC in the early 1950s, as a performer on network television programs and commercials, and as a cable-television producer.

Warhol’s embrace of popular culture was motivated not just by fascination and grudging respect, but by an imperative to question its limitations and push it to its limits. As he challenged television’s conventions and taboos—introducing overt and confident gay sexuality into a commercial sphere virtually devoid of it, for example—he did so in front of a vast national audience.

Television’s enormous cultural reach provided Warhol with the most direct path to influence and fame—his own fifteen minutes—the period in the spotlight to which each person, he believed, was entitled.

In 1968 Warhol directed The Underground Sundae, a television commercial for Schrafft’s, a national restaurant chain. The piece was done in the style of his countercultural movies. Frank G. Shattuck, president of the company, later remarked, “We haven’t got just a commercial. We’ve acquired a work of art.”

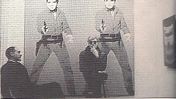

(Above) installation view, Revolution of the Eye, NSU Art Museum Fort Lauderdale, October 2015. Courtesy of the NSU Art Museum

“THE FEW TIMES IN MY LIFE WHEN I’VE GONE ON TELEVISION, I’VE BEEN SO JEALOUS OF THE HOST THAT I HAVEN’T BEEN ABLE TO TALK. AS SOON AS THE TV CAMERAS TURN ON, ALL I CAN THINK IS, ‘I WANT MY OWN SHOW . . . I WANT MY OWN SHOW.’”

ANDY WARHOL

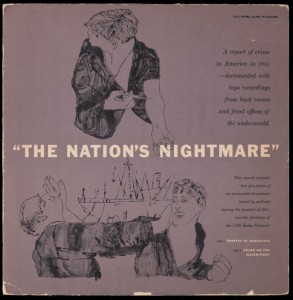

Andy Warhol, The Nation’s Nightmare, CBS Radio, 1952. Album cover and paper label for vinyl record. Private collection

In the early 1950s Andy Warhol designed title art and advertisements for CBS and NBC. He received his first Art Directors Club award for this album cover and record label design for The Nation’s Nightmare, a 1952 CBS radio program about teenage drug use. A year later, Georg Olden, director of graphic design at CBS, named Warhol one of the top twelve graphic designers for television.

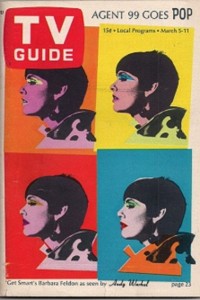

Andy Warhol, cover art for Get Smart, TV Guide, March 5, 1966

Warhol designed a cover of TV Guide devoted to the hit comedy Get Smart. Created by Mel Brooks and Buck Henry, the series satirized the then-popular secret-agent genre, typified by James Bond films and the TV dramas I Spy and The Man from U.N.C.L.E.

Installation view, Revolution of the Eye, NSU Art Museum Fort Lauderdale, October 2015. Courtesy of NSU Art Museum: art from left to right: Andy Warhol, Scotch Broth: Campbell’s Soup Series II, 1968, Serigraph, 38 3/8 x 26 3/8 in. Collection of NSU Art Museum of Art Museum, Fort Lauderdale; Andy Warhol, Mao Series, #1-10, 1972, Silkscreen. Collection NSU Art Museum Fort Lauderdale

Andy Warhol in Braniff Airways commercial with Sonny Liston, 1968; screen captures: Andy Warhol, interview, USA Artists, WNET, New York, March 8, 1966; Andy Warhol on The Love Boat, October, 12, 1985

Warhol made frequent appearances on television, in commercials as well as on talk shows, public-affairs programs, and the hit ABC dramedy, The Love Boat.

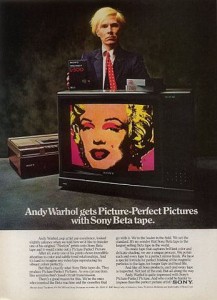

Andy Warhol, Advertisement for Sony Beta videotape, 1979

Andy Warhol on Television

Andy Warhol also made fine art about television, including paintings ($199 Television, 1961), prints, and the short film, Soap Opera (1966), the latter even including fake commercial interruptions. In Outer and Inner Space, Warhol’s first double-screen film, he featured the socialite, actress, and model Edie Sedgwick in front of a television monitor on which is playing a prerecorded videotape of herself. The two segments are spliced together to create a split screen with four close-ups of the actress. Two of the images show Sedgwick speaking spontaneously into the camera, while the other two record her speaking to someone off-screen, commenting on watching herself on television.

“A WHOLE DAY OF LIFE IS LIKE A WHOLE DAY OF TELEVISION. . . . AT THE END OF THE DAY THE WHOLE DAY WILL BE A MOVIE. A MOVIE MADE FOR TV.”

ANDY WARHOL